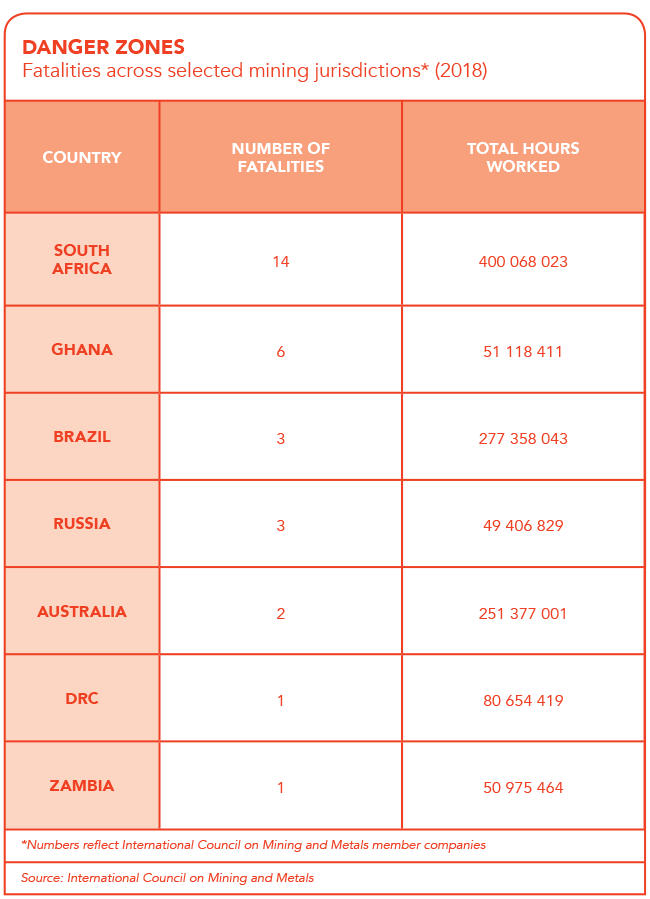

Mining has always been a tough operation. It’s hot, dark and dangerous – and the deeper you dig, the more high-risk it gets. Miners are digging deeper by the day… and, in many cases, the job is becoming more and more perilous.

‘Mining safety is an ever-present concern for mine operators, and we are seeing more of our clients with a strong appetite to adopt tools that can help improve the safety of one’s staff,’ says Leon Cosgrove, mining partner for Wipro Technologies.

‘To deal with these forces, there’s a surging interest in digital solutions that improve the productivity and safety for mine employees. The humble helmet sits at the centre of such innovations. Helmets can become far more than merely a piece of safety equipment, with the likes of connected cameras; augmented-reality apps; sensors to detect dangerous gases or record heat levels; accelerometers; voice-to-text microphones; and collision-detection to alert miners of any potential threats. Modern, smart helmets represent a hands-free way for miners to improve the way in which they work.’

Yet what if technology could take the miner far away from the danger? What if there was a way to get the job done, without sending human beings down to the proverbial coalface?

You’ll find the answer in a fairly dull-looking office building in Thunder Bay. Here, in North-western Ontario, a small group of mineworkers sit in air-conditioned offices with carpeted floors and coffee machines, doing the (no longer) dirty work of moving thousands of tons of rock from Musselwhite mine, located 500 km north, and just more than a kilometre deep. They use video screens and joysticks to operate the machinery, making it all look like a video game.

Goldcorp, which operates the mine, is pioneering remote mining through its new integrated remote operations centre (IROC). The IROC is connected to the mine via a dedicated fibre-optic line, linked to a specialised WiFi infrastructure in the mine itself. Lag time is a low 0.02 seconds. The miners are essentially working in real time.

By physically removing the human workers from the mine site, using data, sensors and remote-control machinery instead, Goldcorp is turning its underground miners into remote miners – and getting the job done faster and more safely than before. ‘I’ve had this vision of trying to get as many people off-site as possible,’ Musselwhite mine’s GM Peter Gula told the local Sudbury Mining Solutions Journal.

‘Every person that we have up at site has about a CAD40 000-a-year cost associated with it. That includes travel, housing and all the staff and services that go to support the people working at Musselwhite.’ He added that the company’s medium-term goal is to move about 60 people from Musselwhite mine to the remote centre at Thunder Bay, which would reduce operational expenses by CAD2.4 million per year.

Part of the cost lies in wasted time. The mine ramp is nearly 15 km long, and workers have to travel for about an hour and a half just to get from where they start their shift to where their equipment is. Add in a blast time, and you’re only getting seven hours of actual work out of a 12-hour shift.

Cost, then, is one driver. Safety is another. ‘First and foremost, we’re removing people from those hazardous conditions,’ said Gula. ‘That’s the best way to control it. You engineer out the problem. You don’t even put them in that environment.’

The miners themselves are pretty happy about it, too. In an interview with local television station TVO, 58-year-old mine employee Carl Johnson looked up from the video screen and admitted that this was his first-ever office job. He’d spent most of his working life in mining camps, two weeks on and two weeks off. Now he’s at home with his family every night. ‘I’m a white-collar worker now,’ he said. ‘If you’d told me this back in ’79 when I started mining, I would have said you have rocks in your head. It’s impossible. Yet here it is.’

It’s easy to see the attraction. In March, independent consultant and Mining Equipment Manufacturers of South Africa (Memsa) board member Paul Jourdan told the Southern African Mining Supply Chain Conference and Strategy Workshop that South Africa needed to devise systems of using remote equipment to mine ultra-deep mines, urging companies to stop sending people down dangerous deep-level mines.

The future application of remote mining machinery is already being seen at the futuristic Syama gold mine in Mali. Located 300 km south-east of Bamako, the mine is operated in large part by driverless vehicles and autonomous equipment, with remote operators overseeing operations from the safety of a control room on the surface. According to John Welborn, CEO of Syama’s Australia-based owners Resolute Mining, one human operator in that control room can supervise up to eight trucks remotely.

Remote mining and autonomous technologies overlap, though, during the notorious ‘smoke hours’ that happen while dust is settling after a blast. Syama has virtually eliminated those, as its driverless trucks are guided by lasers rather than visual cues – making the dust a non-factor. Now, instead of having to work blindly, relying on radio contact with the underground teams, mine operators on the surface can use CCTV and sensor data to visualise the location of the underground assets in real time.

Speaking to the Diggers and Dealers Mining Forum in Western Australia recently, Welborn dismissed the idea that mining automation would cost jobs at the African mine. ‘Automation is often seen through the prism of a vehicle factory where you blow the whistle and sack 200 of your assembly line workers and replace them with robots, or a large group of sewing machine operators who can be replaced by a machine,’ he said. ‘I often get asked about the political impacts of automation in Africa, with the perception that governments will be concerned we’re laying off workers. What we’re doing has very little to do with reducing the workforce. It has everything to do with efficiency and productivity.’

And, of course, safety. Iniel Dreyer, MD of data management company DMP South Africa, sums up the value of data management – particularly in a mining environment – in a recent online post. ‘Mistakes in the mining industry are costly, not simply from a monetary perspective but also from the view of the human lives at stake,’ he writes.

‘Digital transformation has had a significant impact, and the ability to collect and analyse sensor data generated from equipment in particular, can assist to improve safety in mining environments. ‘Underground temperatures and levels of harmful gases can be carefully monitored in real time, equipment can be maintained before it breaks, and dangerous situations can be predicted before they can cause injury or loss of life.’

That’s why underground connectivity is so important – especially when it comes to remote mining operations. Swedish mining company Boliden, together with tech company Ericsson and mobile operator Telia, recently deployed the world’s first 5G NR (new radio) network in an operational underground mine, at Boliden Kankberg.

5G technology offers low response times and the option of local data handling – both of which are vital in demanding environments such as mining, where you need continuous operations and close monitoring of processes. ‘Industry 4.0 is becoming a reality,’ says Magnus Leonhardt, head of strategy and innovation at Telia.

‘This is another good example of how 5G can be used to build networks adapted to the customer’s operations. To guarantee safety in the mine, for example, the network must function even if communication to the outside world is disrupted. Reliable communications can now be secured with the network we have built.’

That quote would have been met with a wry smile at Australia’s Christmas Creek iron ore mine, where two large driverless trucks collided recently. Mine operator Fortescue Metals Group said the accident occurred when the WiFi link between the trucks and the control centre dropped.

The big takeaway from that small crash was that nobody was injured. Of course not: the human drivers were sitting safely in the control centre, far away from the accident scene and out of harm’s way.