Following interviews with executives from more than 350 companies, a 2018 DuPont Sustainable Solutions (DSS) survey concluded that executives, including those in high-hazard industries such as mining, metals and oil, aren’t adequately identifying and preparing for risks that may be potentially catastrophic to business operations.

The 2018 Global Operations Risk Survey of Corporate Leaders showed that while 78% of executives agreed that low incident rates don’t correlate with reduced risk, two-thirds acknowledged feeling satisfied when they saw data indicating incident rates as zero to low. ‘Executives seem to be allowing low incident rates to provide a false sense of security and are ignoring other indicators of potential significant events,’ says DSS in a 2019 media release. Furthermore, the report indicates that internal procedures are insufficient to manage current risks, and 40% of executives admitted to challenges in implementing effective employee-performance management.

Speaking at a panel discussion with mining executives at the recent Mining Indaba, Johan van der Westhuyzen, DSS regional director for Turkey, Middle East and sub-Saharan Africa, said that while executives are aware of the necessary characteristics and procedures for a successful risk-management programme, they are still failing to implement these critical measurements and requirements down to the front-line of the organisation. However, Kenneth Cameron, director of MacRobert Attorneys, says in many cases, the opposite is true.

‘While mid-level managers grapple with day-to-day legal complexities on maintaining a licence to operate, key detail on these matters often do not sufficiently transition to the board,’ he says. ‘Mining entities therefore run the risk of driving critical decisions from two different sets of assumed facts or objectives. As a further result, well-conceived legal strategies are often not implemented successfully and may fail at the very first point where a necessary iteration is required at executive level. There is, however, no reason why a solid commercial agenda cannot be successfully aligned with legislative and regulatory realities.’

Wessel Badenhorst, a partner at law firm Hogan Lovells, says it’s a fine balance between risk and reward in the quest to maximise return on investment. ‘Risk is part of daily life in a mine. Mines and the safety inspectorate spend most of their effort to manage that risk and to train mineworkers to identify [it] in an attempt to avoid risk where possible and to mitigate [it] where it is unavoidable,’ he says.

External business risks come in many forms. ‘There are volatile commodity trading patterns and prices, exchange-rate fluctuations, changes to mineral laws and the enforcement thereof, and myriad political risks associated with the sensitivities of mining in close proximity to communities and labour-sending areas,’ according to Badenhorst. Risk management is thus part and parcel of everyday operations in the industry. ‘Do it badly and it will wreak havoc with the future stability of the business,’ as evidenced by incidents in South African mines that to this day continue to haunt the mining companies involved. ‘Manage risk well, and you will be able to avoid risk where possible and mitigate against its adverse effects where altogether unavoidable.’

The Department of Mineral Resources in South Africa has made progress by removing the uncertainty around the third Mining Charter, says Badenhorst, but more must be done in clarifying regulatory uncertainty, thereby reducing risk to the industry. ‘Recent controversial court decisions regarding the rights of communities to consent to mining have not helped to stabilise the risk environment.’

Considering the risks that stretch beyond the industry’s collective control, such as international commodity demand and fluctuations in our exchange rate, the industry must focus on eliminating the domestic risks it can control. ‘If we fail, the future of the South African mining industry, as a sunset industry, looks bleak and frail,’ he says. ‘Now, more than ever, mining companies need to enlist all the help they can get to minimise risk, and risk-advisory firms have a major role to play in advising the industry, as do the risk departments of financial institutions and insurance companies. Sharp, well-researched and current risk models should be mandatory reading for all mining executives.’

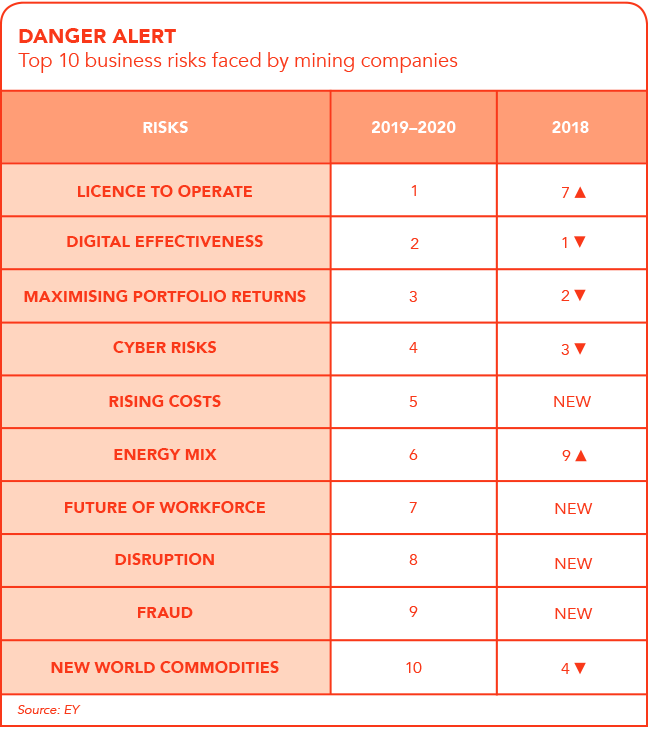

The top risks facing mining and metals in 2019/20 reflect a new era of disruption from both within and outside of the sector, states EY Global mining and metals leader Paul Mitchell on the company’s website, in reference to a survey of the 10 business risks facing companies in mining and metals. Among the top risks are a licence to operate, digital effectiveness, maximising portfolio returns and cyber risks. ‘The large movements across the radar are clear indicators that disruption is already here,’ writes Mitchell. ‘Societal change, new technologies and the race to transform business models are driving a whole range of disruption for mining and metals companies. Pressure on technology and automotive companies to secure the supply of New World commodities is opening another avenue of potential disruption to current business models. Over 30% of our survey respondents thought that technology companies have the potential to disrupt the sector. We agree. They have good access to capital and are already investing in the innovation and technology that mining operations need to be more effective.’

Also speaking at the Mining Indaba, July Ndlovu, CEO of Anglo American Coal South Africa, explained how even with a number of risk-reducing safety measures in place at the company’s mines, it recorded three fatalities in 2017. ‘We stopped all 10 mines and talked to our 16 000 employees to find out what was going wrong,’ he said. ‘While there was nothing wrong with our processes, what it came down to was being able to identify the lack of leadership capability at the front-line. When an operator or artisan is promoted to front-line supervisor, they need to develop the necessary skills to also be a leader. What we learned, as a mature organisation, we must have the systems and processes in place in order to improve, but the focus should be on culture. We have to ask ourselves the question: How do we make the system come to life at the ground level?’

Suran Moodley, MD of strategy and organisational capability at Ariston Global, a business advisory firm, says one would be hard-pressed to find a mining company without an enterprise-wide risk-management committee, given the ubiquitous physical hazards faced by miners and the financial risks that have materialised in recent times. And new threats are emerging with the introduction of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, she says.

‘Risk committees need to now look beyond finance, HR, occupational health and safety, industrial relations and environmental risks. The development of autonomous vehicles, artificial intelligence and drones could offer solutions to industrial relations as well as health and safety challenges, but may adversely affect unemployment, communities dependant on mining operations and contribute to political pressures and social degradation if not managed correctly,’ says Moodley. ‘We consider how technology and digitisation would affect a largely labour-intensive environment. While there are benefits in terms of health and safety, what are the impacts for employment and reskilling existing employees so as to not contribute to large-scale unemployment? Furthermore, are there sufficient skills for the new equipment that will be deployed in mining operations?’

She also warns that while more jobs may be created, they will be in the areas of mechanical engineering, programming, IT and communications, which means that mining companies are facing massive education, training and development requirements. The immediate opportunity for external risk advisers, according to Moodley, is to begin a programme of up-skilling general labour to meet the demand of technological advancements. ‘This needs to be embedded in programmes of change management with strong emphasis on stakeholder management,’ she says. ‘With the tragedy at Marikana fresh in our memory, the volatility in this sector can’t be overemphasised.’ The responsible implementation of technology and AI is another area in which consultants and advisory firms can add value.

The ISO 31000 risk-management guide defines risk as the effect of uncertainty on objectives, notes Mtutuzeli Buwa, CEO of Ndalo Risk Management. Organisations that are acutely aware of their risks tend to thrive and survive even in trying times, he explains. ‘Mining organisations should incorporate risk consideration in their planning and decision-making at all levels of the organisation,’ he says. And this process should be influenced by best practice provided in international standards and guidelines.

There are two widely used standards, the COSO and ISO 31000, both of which suggest a similar approach to risk management. First, understand the business context, then undertake a risk-assessment exercise.

Mining operations always begin with an initial exploration to see if it is indeed feasible to mine a specific area. ‘Essentially, this is a risk-management tactic as it seeks to determine whether or not there is a business case for starting mining operations,’ says Buwa. One of the key plans to be prepared by mining companies is the environmental assessment plan (EAP). Part of this plan is the rehabilitation of the surface after the mining operations have ceased, or the protection of the environment from the negative effects that may result from these operations. ‘A risk-assessment exercise is important as it gives stakeholders the pros and cons that have been evaluated and what the best action is for design and implementation.’

Once operations have started, continued risk profiling is necessary to help avoid interruptions to business, which can result from issues with ongoing day-to-day operations or from external events over which the company has little or no control. According to Buwa, ‘understanding these events and their impact on operations is critical to the resilience and continued existence of business’.

Insurance companies and consultants have an opportunity to help shape the decisions of organisations, especially in mining because of the high overhead cost of establishing support functions, which lead many operations to outsource these functions. ‘Mining companies need assistance with continuous training to help manage occupational, health and safety issues,’ he says.

He advises these companies to tailor their solutions to the industrial needs while considering international practices, global economic imperatives, local legislative and developmental strategies, and community impact analysis and plans. ‘Service providers should have a local footing and appreciation of politics and developmental goals while maintaining a global perspective,’ says Buwa. ‘The products and services should meet international standards and benchmarks, which include compliance to standards and laws that relate to the mining sector.’