There’s a new sound among the cacophony of noise around Kumba Iron Ore’s Sishen mine in the Northern Cape. Between the drilling, blasting and loading, you’ll now hear the gentle whirring of a small fleet of unmanned, remotely operated aerial drones in the skies above the mine. Those drones use on-board cameras and laser scanners to create three-dimensional images of ore to calculate volume, and to survey accident scenes and areas deemed unsafe for workers. And while those airborne drones fly about, their pilots will be located in relative comfort and safety, in a control room away from the mine’s more dangerous environments.

Kumba’s executives expect operations to become significantly safer as a result – which is precisely why the Anglo American subsidiary applied for the licence to operate those survey drones in the first place. ‘This licence allows us to operate our own drones, with our own pilots, at heights of up to 1 000 feet,’ Kumba technical manager Bongi Ntsoelengoe said in a media statement in July 2018. ‘We worked through two years of complex legal, governance and logistical challenges to earn an operating licence to fly our remotely piloted aircraft systems and the technology is already proving a game changer at our Sishen mine.’

Ntsoelengoe added that routine tasks around the mine that were previously carried out by surveyors – such as measuring the volume of stockpiles – are now being done by those drones. ‘The drones collect digital imagery that is pieced together to perform volume calculations, giving us reliable data without having to put anyone at risk,’ he said. Kumba’s licence came at the end of an onerous two-year accreditation process. The company – like many others – had been using drones since 2015 but only through third-party service providers. Kumba had to overcome a series of legislative and regulatory hurdles before its own pilots could operate the company’s fleet of drones.

In simple terms, South Africa’s Civil Aviation Authority sees commercial drones as equivalent to manned aircraft, so they require a licence to own (renewable every 12 months) and a remote pilot’s licence to fly (renewable every 24 months). Those restrictions have clipped the wings of many mine operators that want to use drones for their own purposes but find the licensing process to be more of a hassle than it’s worth.

Still, it’s clearly worth a lot to miners to have a cheaper, safer and more efficient way of doing business. Between 2014 and 2017, Kumba spent a reported ZAR748 million on new technologies in a part of a wider initiative by Anglo American, whose investment in new technologies includes introducing survey drones and remote-controlled drills to improve miner safety by physically distancing workers from potentially dangerous tasks.

‘We believe that technology is a potential game changer for Kumba,’ Anglo states its 2017 integrated report. ‘Through our technology strategy, we seek to accelerate the adoption of appropriate technologies at our operations to improve safety to achieve our zero harm target; drive down costs by improving productivity and efficiencies; and maximise current and future resource utilisation through the development of low-grade beneficiation technology.’

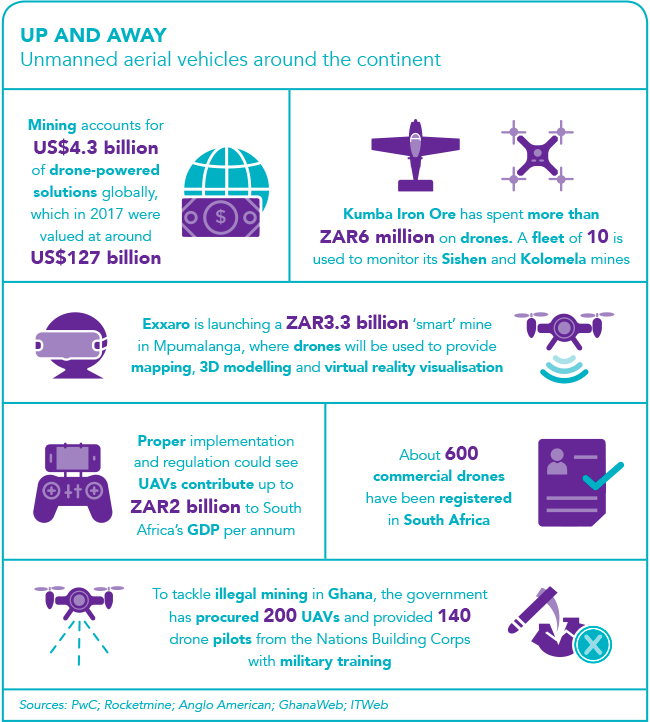

For Kumba and Anglo, read: everybody. Mines and mining houses across Africa – and, indeed, across the world – are stepping up their development and implementation of drone and unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) technology as a means to drive costs down and efficiencies up. Drones are generally cheaper, faster and safer than traditional survey methods – and the list of drone applications continues to grow as the technology develops.That, of course, is good news for South Africa’s accredited UAV operators. Soon after Kumba’s fleet took flight over Sishen and sister mine Kolomela, local operator Rocketmine announced that it had secured contracts to provide terrain surveying, stockpile inspection, blast monitoring and mapping services to mining companies in Southern and West Africa.

In Namibia, Rocketmine will enable the Rio Tinto-owned Rössing Uranium mine to achieve the best possible grade of uranium by using data-gathering drones to optimise the accuracy of planning and inspecting. The company will also provide mine blast monitoring and fragmentation analysis and survey mapping to Newcrest Mining in Côte d’Ivoire and Newmont Akyem in Ghana; and survey and mapping solutions to the Exxaro Resources Group’s Grootegeluk mine in South Africa’s Limpopo province. Grootegeluk is Exxaro’s largest opencast mine in the southern hemisphere, with various dangers to human surveyors.

‘A global cumulative amount for these African projects over the next three years equates to nearly EUR1 million,’ according to Rocketmine MD Christopher Clark. ‘These mines are clear cases that the future of mining will utilise technology not only to find innovative solutions but to decrease mines’ carbon footprint.’

As the global market for UAV operations grows, the technology will also continue to develop and improve. Industries such as agriculture, construction, filming and mining – all of which were early adopters of drone technology – appear poised to benefit the most. ‘Right from the beginning there was quite a bit of interest in our service from the mining sector,’ says Kuben Govender, sales director at KwaZulu-Natal-based drone services company DC Geomatics.

‘A lot of that interest came from the open-pit mines, where they needed to do regular volume surveys.’ Since then, DC Geomatics’ list of mining-specific services has expanded to include everything from aerial mapping and scoping to industrial inspections, topographical assessments, progress-monitoring photography, strip surveys and as-built surveys, ground-penetrating radar, LiDAR (light detection and ranging) surveys and more. ‘We have a new drone-based technology that we use in the plant environment, mostly for inspections,’ says Govender. ‘Although there may be restrictions in how you can move the drone between fixed structures, many modern drones are equipped with proximity sensors and can safely fly in those areas.’

While Govender is speaking specifically about airborne operations, there’s a growing awareness across the industry of the need for drones to fly under the ground too. Subterranean drones, however, have struggled in the past to navigate the dark, confined spaces typical of underground mining environments – especially when those environments are not conducive to the satellite-based GPS signals that drones typically use to navigate. Yet that too is changing.

In late 2018 Australian start-up Emesent raised US$2.5 million in funding for its Hovermap system, which enables autonomous drone mapping of underground mines without the use of GPS. As reported by TechCrunch, Hovermap fits standard, off-the-shelf DJI drones with LiDAR sensors and an on-board processor, and then uses simultaneous localisation and mapping (SLAM) technology to provide the drone with the spatial awareness it needs to fly safely. In a TechCrunch article, Emesent CEO Stefan Hrabar explains that underground drone mapping will save miners from doing the ‘dull, dirty and dangerous’ work by using specially equipped autonomous drones instead.

This, he says, is particularly important during stoping, where ore is blasted out of the vertical space between two tunnels. ‘The way they scan these stopes is pretty archaic,’ according to Hrabar. ‘These voids can be huge, like 40m to 50m horizontally. They have to go to the edge of this dangerous underground cliff and sort of poke this stick out into it and try to get a scan. It’s very sparse information and from only one point of view; there’s a lot of missing data.’

He explains that using drone mapping technology the surveyors aren’t at risk and the data is ‘orders of magnitude’ better. ‘Everything is running on board the drone in real time for path planning,’ he says. ‘That’s our core IP. The dev team’s background is in drone autonomy, collision avoidance, terrain following – basically the drone sensing its environment and doing the right thing.’ While Hovermap is still a fairly new technology, any geologist’s toolkit would benefit from a system that can accurately and autonomously provide a digital model of an entire subterranean environment. ‘At the end of the day, mining companies don’t want a point cloud; they want a report,’ says Hrabar. ‘So it’s not just collecting data but doing the analytics as well.’

DC Geomatics’ Govender, meanwhile, points to another area in which drones are proving their value to mining companies: security. A point that is often lost on people outside the industry is just how massive a mine’s operating area really is. In almost every case, it’s neither practical nor possible to have a guard with a flashlight patrolling the site. ‘We’ve seen a big shift recently from surveying to security,’ says Govender.

‘Many of our clients are looking at drones to serve as an additional, affordable surveillance tool for their security centre. You can see why that would be: from a security management point of view, it’s quite advantageous to have the bird’s-eye perspective that a drone provides, rather than relying on a person on the ground. Safety is also a concern: if there are on-site protests at your mine, you would want to deploy drones rather than human security teams to monitor that activity.’

Again, the utility lies in being able to send an unmanned drone into an environment that’s either unsafe for, or unreachable by, humans. And, as the mining industry as a whole becomes safer, cleaner, more digitalised and more automated, the possibilities of this technology will be pushed ever further.